<<<BACK TO PART ONE

"Ramming Speed!"

Naval Battles of

the Ironclad Emperor of the Pacific, PART TWO

The Smaller

Peruvian Ironclad Huascar receives a raking fire from

the Chilean

Ironclad Frigate Almirante Cochrane at the Battle of Angamos,

1879.

Two years after the Huascar’s dance with the Royal Navy,

fertilizer again caused a war. Bolivia had allowed Chile to mine

nitrate-rich saltpetre in their territory. Against the terms of a

treaty signed between the two nations, Bolivia introduced a tax on

the miners. Chile protested and the diplomatic row escalated to

war. An ally of Bolivia, Peru tried to mediate the conflict but was

ultimately dragged into war against Chile.

Naval supply lines were critical to conduct a war against Bolivia,

and Chile quickly sought naval supremacy. In an effort to settle the

matter, Chile sailed its fleet to the major Peruvian port of Calleo

and engaged in a major sea battle. Chile left behind two older

wooden warships to blockade the smaller port of Iquique. On the

morning of May 21,1879 two plumes of smoke were spotted through the

morning fog off Iquique. Cutting through the mist were the bows of

the Huascar and its sister British-built ironclad, the

Independencia. An exchange of artillery fire immediately

commenced between the Huascar and the Chilean frigate

Esmeralda. Interestingly enough, barely a decade had passed

since the Esmeralda had fought alongside Peru and Chile

against the Spanish. Friend had become foe.

The Esmeralda was hit almost immediately with a round passing

through its hull, killing the surgeon and beheading his assistant.

The Esmeralda soon repositioned herself with the Peruvian

coastal town behind it. The Huascar’s crew hesitated to fire,

concerned that the rounds might hit civilians watching the battle on

the shore. Suddenly taking fire from the garrison troops in

Iquique, the Esmeralda pushed its

engines to adjust to the new threat from land. The move blew one of

its boilers leaving the Chilean ship limping along. Noticing the

Esmeralda had no torpedoes, and knowing its own iron was

impervious to the enemy’s artillery, the Huascar steamed in

for the kill.

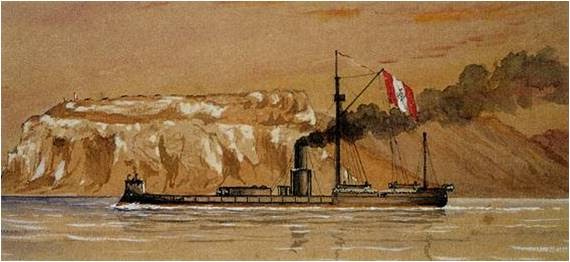

Black smoke rolling from its chimney, the

Peruvian Ironclad Huascar reaches ramming speed as it closes

on the Chilean Corvette, Esmeralda

As Huascar’s ram cut towards the Esmeralda, the

Chilean crew successfully maneuvered their crippled ship to minimize

the blow. The Huascar responded by unleashing a point-blank

volley from its massive Armstrong guns into the Esmeralda.

Dozens of Chilean sailors and marines were blasted into eternity.

Chaos and exchanges of small arms fire ensued. When the smoke

cleared, the Esmeralda’s captain was dead, and his body lain

on the deck of the Huascar.

Witnessing the Esmeralda ‘s desperate situation, Captain

Miguel Grau of the Huascar gave the remaining Chilean crew an

opportunity to surrender. Grau would become to be known as “the

Gentleman of the Seas” for his chivalrous conduct towards his

enemy. Unfortunately, the Chilean crew opted to respond to Grau’s

calls for surrender by nailing the flag of Chile to the

mizzen-mast. It was a statement that the Esmeralda would

never strike its colours and surrender.

Respected by both

friend and foe for his honourable conduct, Admiral Miguel Grau became known

as "The Gentleman of the Seas".

Given little choice, Grau brought the Huascar to ramming

speed and charged again at the Esmeralda. This time the

Peruvian ironclad crashed through the starboard side of the Chilean

warship and water poured into her powder magazine and engines.

Again, the Huascar unleashed a volley from its mighty Armstrong guns

with lethal effect, destroying the Esmeralda officer’s mess

and partially clearing the deck of its crew. The Esmeralda’s

crew bravely jumped aboard the Huascar with machetes and rifles in a

vain attempt to seize victory from the ironclad jaws of defeat. The

Huascar’s gatling gun crew made short work of the Chilean

boarding party. Nobly the ironclad’s captain had the lone survivor

rushed to the Huascar’s infirmary.

Surprisingly, throughout this, the Esmeralda remained

afloat. Twenty-minutes later the Huascar rammed the Chilean

warship a third and final time right under the mizzen-mast. A last

defiant cannon shot was fired before the Esmeralda sunk into

a watery grave. The final part of the ship to disappear was the

Chilean flag nailed to the mast.

The Huascar

rams the sinking Esmeralda the third and final time.(Thomas

Somerscales)

Though exhausted the work of Huascar’s crew was not over.

The other Peruvian ironclad had ran aground exposing its stern and

could not bring its guns to bear. Another Chilean warship had

successfully positioned itself in close and turned the

Independencia into scrap metal. The Huascar steamed to

its rescue and chased the enemy vessel off.

While the Battle of Iquique was a great victory for the Huascar,

Chile still possessed a vastly superior navy, complete with more

modern ironclads and armaments. Capitan Grau, now an Admiral, turned

to guerilla tactics of striking fast and retreating. Like a ghost,

the Huascar played havoc on the Chilean supply lines by

attacking out of nowhere and then disappearing. These stings to

Chilean shipping became too much to bear. One contemporary wrote:

“the Chileans had bent all their energies on capturing the waspish

little ironclad, which had kept their coasts in a continual state of

terror.”

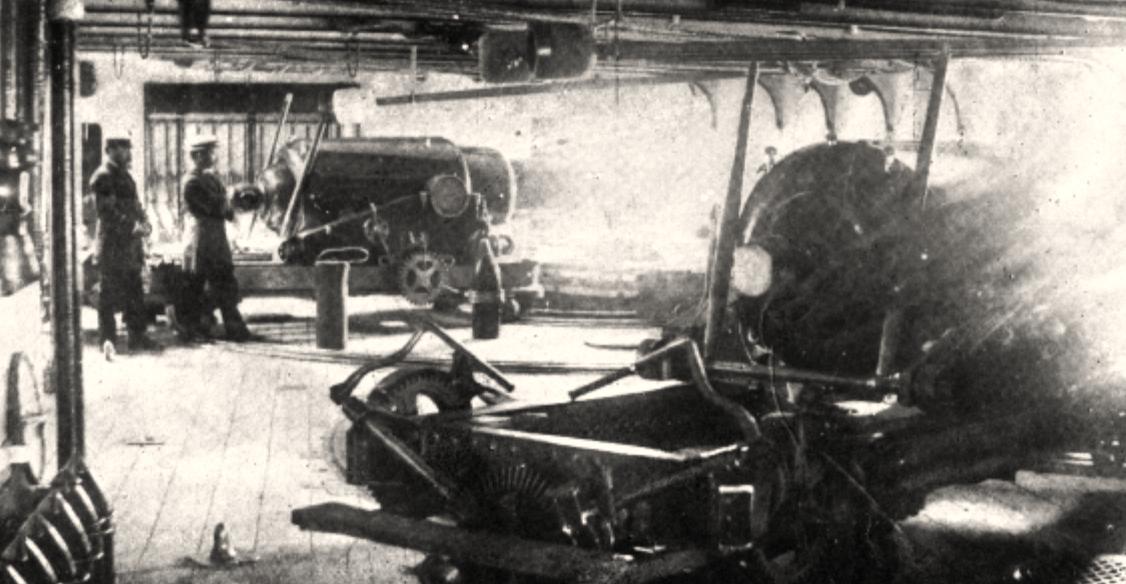

Deck of the

main four-gun battery of the British-built Chilean Ironclad Frigate

Almirante Cochrane.

After a long chase, the Chilean fleet of six warships including two

of the most powerful ironclad frigates in the Pacific finally

cornered the spirited Huascar on the morning of October 9,

1879. The world’s first pitched battle between sea-going ironclads

began with the Peruvian ironclad firing shots at the (also

British-built!) Chilean frigate Almirante Cochrane. As the

Chilean ship closed in, Admiral Grau had little choice but to use

the Huascar’s superior speed and try to run past the Chilean

fleet.

The Captain of the Almirante Cochrane held his fire until the

distance closed to a mile and a quarter. Loaded with new

armour-piercing rounds, the Chilean ironclad unleashed destruction

on the smaller Huascar. Positioned slightly to the stern of

its target, the shells of the Cochrane had an immediate

effect. The very first shot pierced the Peruvian gun turret injuring

the entire gun crew. Another round disabled the rudder and the crew

of the Huascar scrambled to regain control of their vessel.

Shortly after repairing the rudder, tragedy struck. A shell hit the

bridge cabin killing the noble Admiral Grau. Command of the

Huascar fell to Capitan Aguirre. The punishing bombardment

continued from the Cochrane. The Huascar’s stern was

on fire and the rudder wheel destroyed. The crew in the forecastle

were wiped out. Peruvian casualties were piling up.

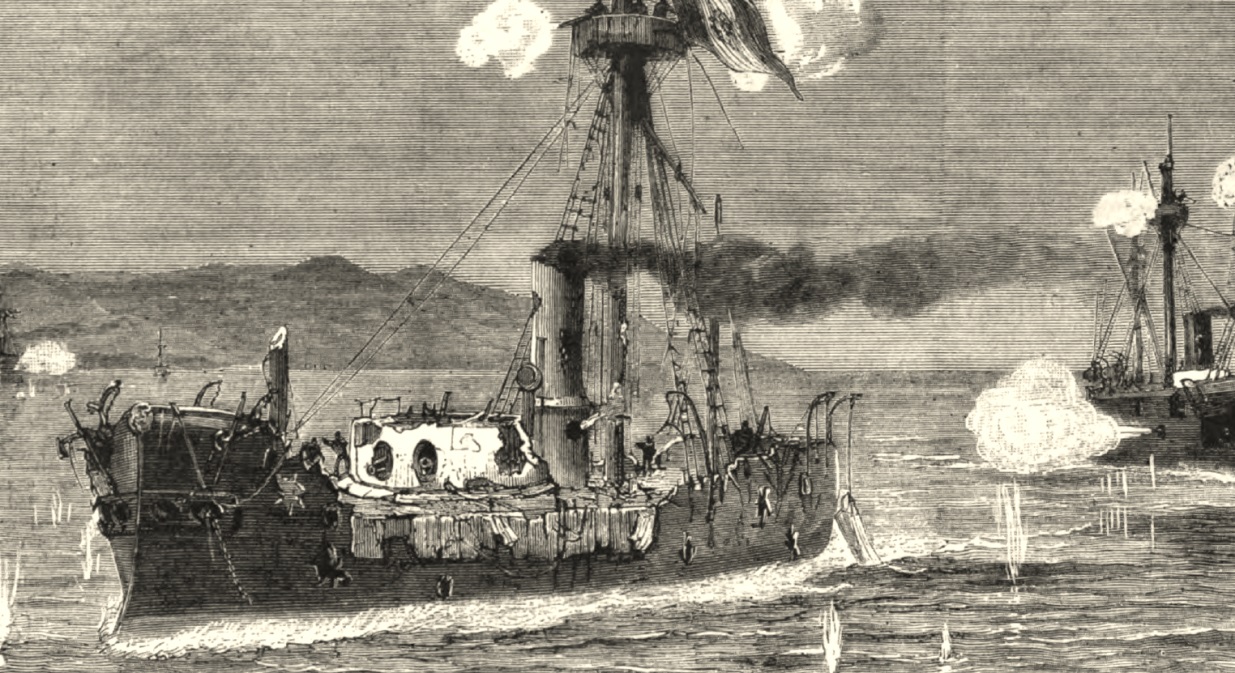

Two

Chilean

Ironclad Frigates pound away at the noble and defiant Huascar Two

Chilean

Ironclad Frigates pound away at the noble and defiant Huascar

When the Peruvian flag was knocked from its hoist, the Chileans

ceased firing thinking the Huascar had surrendered. But the

gallant Peruvian crew hoisted the flag again and the battle

continued. At this time, the Cochrane ‘s sister ship, the

Blanco Encalada joined the battle by firing a shell into the

Huascar’s turret, killing many of the crew and destroying one of the

guns. A round from the Cochrane smashed through the officer’s

quarters, again temporarily disabling the rudder.

Once steering control was again possible, Captain Aguirre, out of

desperation, tried to ram the Cochrane. Coincidentally the

captain of the Cochrane had the same idea but both ships

missed each other. Twelve minutes later, yet another shell pierced

the Huascar’s gun turret killing everyone inside, including the

captain. Rather than allowing it to be capture, the next in command

ordered the Huascar scuttled. Accordingly, the main valve

was opened, and the Peruvian ironclad began to take on water.

As the

Huascar slowed, the Chilean warships were able to come along

side and board her. There was no resistance. Of the 200 members of

Huascar’s crew, 78 were killed and another 30 were wounded.

The Chileans were able to close the valve and stop the ship from

sinking. In a fate similar to it’s Incan Emperor namesake, the

Huascar had been captured by its enemies.

The extent on damage to the Ironclad Huascar.

Half her crew were killed or wounded.

As

a sign of respect, the captured ironclad was allowed to keep its

name. It was renewed and strengthened with new armaments and

engines. Nine years after the Esmeralda was sunk, the Huascar

returned under the Chilean flag to recover the bodies of its

crew. The Huascar continued to serve in the Chilean Navy into

the 20th Century, when it was converted into a

floating museum. Today the restored ironclad can be visited at

the port of Tacahuano, Chile. The Huascar continues to endure.

|

Author

Robert Henderson enjoys unearthing and

telling stories of military valour, heritage, and sacrifice

from across the globe. Lest we forget.

|

|